Content Warning: This post is a tender retelling of a sensitive childhood story, which makes mention of loss, grief, and alludes to many forms of abuse we can experience, directly, indirectly, or in our communities. Proceed with awareness of your heart and feelings, pause when you need. Take care of yourselves, always.

I am helpless in giving the benefit of the doubt.

It likely comes from a place of believing that someone’s intentions, or the connotation of someone’s intent wrapped in their behavior, can truly be inherently not good, or justified. It is a projection of a core belief that’s been installed in me since early childhood, that I’d internalized and still, to this day, work hard on undoing.

My father used to tell us all the time: “Do no harm, and no harm will be done onto you.” When I once got slapped by a neighbor’s kid—a typical bully lead by xenophobic hatred—I ran to my father crying my eyes out. He asked me: “What did you do to him? You must have said something, or done something to him if he hit you.”

I remember the rage in the pit of my stomach. I remember the fire, the anger towards my word not being trusted. My pain not taken seriously. Moreover, he believed this faceless, nameless individual’s behavior was justified over the pain of his own daughter.

Along came Uncle Yaw, our next-door neighbor. He heard me crying, yelling back at my father, and intervened. When I told him what happened, he grabbed me by the hand and said—”Take me to these jerks”. I remember the feeling in my chest rising up to face my demons, with Uncle Yaw by my side.

We went to their home, a two-storied house at the tail-end of our neighborhood. There, he yelled a full ten minutes to the children, their parents, their parents’ parents—in Serbian, which I could not understand—as they were sitting in their front yard eating watermelon. Their little dogs—who would often chase us down the street, sicced onto us by those same kids—were now hiding behind their owners’ plastic chairs.

I may have smiled a little, feeling a little smug and protected. I may have been terrified, as I had never seen Uncle Yaw this enraged before. I may have been a little wounded, feeling it should have been my father by my side.

Uncle Yaw was a complicated figure in my youth. Everyone was terrified of him—no other neighborhood kid would get close to his home. Yet, most of my childhood mornings or afternoons were in or around its vicinity.

He had a cow named Cassandra, who he let me visit in the daily. She was a quiet lady. I wouldn’t bother her with much, I often went in her shed, placed my hand on her face, looked into her shiny pupils seeking for a source to her… sadness? Grief?

I don’t know what I was looking for in Cassandra, but most every morning, I would go in and ask how she was doing, to say hi. I was lucky if I ever got more than a whiff from her, she’d rarely moo.

Then, I would go into the chicken coops. The little chicks would run around and eventually, when they realized I was no threat, they would get closer. I would sometimes grab them in between my palms and, like with Cassandra, I would seek for their eyes, ask them how they were—to which they would repeat the same sound they always peeped, in a somewhat softer tone: ciu.

I was, however, a very large creature in their very tiny coop. They had every right to be terrified of me, even if my intentions were pure.

Later on, Cassandra was no longer home. I don’t remember what I was told of her whereabouts. Eventually, the chickens and their chicks were gone, too. The garden grew, but their home grew emptier. Their children left eventually. There was only Yaw, and his wife, Aunt Tay.

The neighborhood children hated Aunt Tay. She would always yell at us for playing too loud, throwing the ball around, threatening her windows. In general, she felt threatened by us. She would sometimes spray us with water, just to make us go away.

She kind of liked me—maybe because I was the only girl in our group, quirky and weird—but sometimes she’d give me fruit from her backyard, and tell me I was a “good girl”. I felt conflicted going back to my friends, who would hate on her. I tried to rectify her—”She’s not a bad person, she’s just going through a lot”, I’d say.

Something in her felt like suffering, though I never got close enough to see into her eyes.

One hot summer, we got news that Uncle Yaw had passed away. Heat stroke. It may have been the first death in my life I had to grieve, of a person no one understood why I cared for.

I remembered him as someone who stood up for me when no-one did. Someone who opened the doors to his little animal kingdom, and let me make friends with creatures everyone else seemed to either ignore, or be repulsed by (my sister would threaten to wash me wish a hard-brush each evening when I went home… I likely reeked of a childhood-well-lived…). He did not mind my presence or curiosity.

When they told me of his passing, I imagined myself being the Sun. I looked onto Uncle Yaw, working on his garden, and decided it was time for him to rest. In this fake memory of mine, he laid down to rest in his one-wheel cart. And then the people came to take him.

Aunt Tay grew quieter since. The neighborhood grew quieter, too. Most of the kids now in middle-school, throwing the ball around didn’t impress crushes anymore. Me and my best friend would ride our bikes to far-away neighborhoods most days in corn-seeking expeditions, or I would go on walks with my neighborhood’s stray dogs.

One evening, reminiscing about Uncle Yaw and his small kingdom, I was told:

“He’s not the man you think he was. There is a reason everyone was terrified of him, especially Tay and his children.”

Somehow, I almost begged to differ. In a strange, wordless way a child knows things, everything about Uncle Yaw’s eyes made sense.

I understood the brokenness inside of him like I understood Cassandra’s deep sadness. I understood the jagged edges of his mustached smile and the roughness of his hands, like I understood the baby chick’s fear when I entered their coop. I felt it in Aunt Tay’s anxious cries when asking us to not disturb her peace.

In that deep knowing of a child, I knew exactly the kind of man Uncle Yaw was, but—in that stubborn, persisting innocence of a child—I wanted to believe he, too, could be kind. That if I could show him—…

I wanted to go to Aunt Tay and apologize. I wanted to tell her—I am sorry he didn’t choose to be kind to you. I am sorry he was a monster, too.

“If people knew who he really was, why didn’t they stop him? Why didn’t they help Aunt Tay?”

In the silence that followed, I wanted to go to my father and tell him he was dead-wrong.

I look back on the day I walked into my father’s garage, and was sent back with my tail between my legs. Perhaps my father wanted to teach me humility. Perhaps he did not experience what it meant to be stood up for; maybe he did not believe the solution was to perpetuate violence, and wanted the cycle to end with my rectification.

He believed I could course-correct; that someone’s else’s pain could not be fixed with someone else’s tools. Not my pain, nor the child’s who had hit me that day, nor Aunt Tay’s, nor his own, nor my mother’s, nor my brother’s, nor my sister’s brother…

But—I could change. I could adapt to appropriate a better outcome, because I was his child after all, raised on good principle.

“It had to be you—” he said. “People don’t hurt people without reason.”

I may have disagreed that day, but carried these words nestled in an slow-burning contempt with me right into my therapist’s door, twenty years later.

The cycles played on repeat: I gave it my all, and yet I felt insufficient in what I had to offer to the world. Until something clicked, and I understood that what I truly felt when I showed up in life was: fear.

This was my inner compass’ alignment, it pointed to fear: of failure, of being undeserving of anything more than pain, abandonment, dismissiveness, dejection. Consequently, who I was to be became irrelevant in the face of what was needed from me. This way, I could at least live to prove myself.

My rose-tinted glasses a disease of the blind eye, trained to believe in this made-up reality. It provided someone comfort, once, in my lifetime, and it was enough— I have made it my mission to prove people are worth it.

Outside of this internal haywire, in the world I manifested as a highly sensitive person. In practice this meant—alongside heightened senses of beauty and awe with existence—sometimes a subtle reaction from someone important, or lack thereof, would fire off all alarms within my psyche. My skin buzzing with something that felt like excitement, my smile brighter, wider, my body firmer, my breath slightly hanging at the tip of my chest. Like being called onto the stage—all of my being knowing this was my time to show them, prove to them… what?

That there was a better way to treat people? A safer way to build something together? A kinder way of being with each other? A simpler way to love? A gentler way of life? Integrity in an earnest way of sharing ourselves with the other? That communication is key? That I—you, them, we—deserved better?

What when you lack the skills? What when you lack the willingness to notice? What when you lack the willingness for responsibility? What when righteousness meets reality, and all there is produced is the messiness of existence?

There was a simpler answer to all of this, that after half a decade in therapy I still work hard and untangling the wires that make it feel such a complex understanding of reality: at the end of the line of a person who accepts pain and suffering, is a child that learned they deserve nothing more.

And you see, I had learned better in theory. In practice, I had yet to learn to show up better for myself, but I made a promise to myself. Every week, for now over half a decade, I would show up to explain to my therapist the ways in which I deserved a glass forever half-full.

“What about their glass?” she’d ask me. “Are their glasses full?”

“Well, I tried my best… but it was still not enough. No matter how hard I try, how much I give, it’s never enough. I am simply not enough.”

“Why are you trying to convince them you are?”

“I want them to see they deserve so much more.”

“And you? What do you deserve?”

“What? This isn’t about what I deserve… What difference does that make?”

“How much you are willing to give.”

It is a strange cycle, losing trust in how you understand your reality, the threads of stories which make-up the world around you. At a very young age, I learned that reality is an embroidery sown by the hands most apt to wind its threads.

So—I mastered the art of reading between its lines, to catch intent as if it were a scent. (Mis)Guided by my core principles though, sometimes, the signature on the wall pointed to the mission at hand, and it blurred the warning signs. To this day, I still choose to take people to their words.

I am stubborn with principle.

But words—they simply are not enough. Just as love is not enough, as just a feeling. It begs action, a juxtaposition of reality suffering of itself. Just as our actions—when hidden behind closed doors, when not communicated, when something holds us from exposing them to the light—are not painting the complete picture of our internal truth.

Yes, you may fall in love with a version someone brought onto the light, but have to live with the version behind closed shudders. You may feel comfortable bringing a version of yourself out into the light, but must contend with the one burdening you within closed walls.

The former a version of ourselves that may lead with the socially acceptable intent, for it too wants to be loved. The latter is the one who ends up causing the pain, for it too is so deeply wounded.

But what does it matter to the heart, that there was any rhyme or reason to the hurt experienced?

“Imagine there is a well, and at the bottom of that well is a woman. Every day, on your way to do your bidding, wherever you are going… you stop by the well and look down on this woman. She looks at you, you look at her. You could perhaps help her. But you choose to go to where you were going.

You see, this woman in the well, is also you. And she does not like you very much.”

There was, after all, a way to rebuild this trust in myself, and the environment I subjected it to, now well into my adulthood.

It wasn’t until I was out in the world lead only by my inner compass, that I got to truly understand the impact of my principles. Whether adopted, learned, enforced, habituated to, our lived reality is a direct result of our actions, and they, of our beliefs, and they, of our experience, and it all—a consequence.

consequent(n.)

“a thing which follows from a cause,” 1610s, from a more precise sense in logic, “that which follows logically from a premise”.

Gripping with this reality started an internal battle which made me aware of the war inside. The cognitive dissonance between the lived and believed reality is not as obvious as the word itself suggests—it is a quiet, numbness right in the center of your mind, akin to tinnitus. You do not feel it, or sense it, until the world and everything in it gets absolutely, almost completely, quiet.

When it did, I learned the way out of it was to introduce more noise. But I had, at that point of my life, worked hard to be lucky enough—vocationally and financially privileged—to be in an environment where I could now operate outside of the established rules of my society of origin. So I woke up—and I used this privilege to snap out of self-sabotaging my way right back into pain.

It took time and effort until the grip of shame and guilt of asking for help, of going to therapy, of being vulnerable, of expressing myself… grew weak against the desire to lean into my Self’s point of origin: curiosity, need for expression, wonder, play.

They do say healing is not linear. Life with a broken compass, especially in unfamiliar territory, begged for me to above all be unbelievably patient—with myself, with what was coming, with what I didn’t know was coming, with what I didn’t need to know or understand, with my loved ones... especially the ones I chose to share my inner walls with, and vice-versa.

With every bump and bruise, every ache experienced, it became imperative to my growth that I took a step back, and drew one more dotted line to where a boundary should be.

Eventually, I had a shape of what seemed to form a Self.

Once I trusted this felt true to who I was—not a role I was meant to fulfill, or someone I felt I needed to be— I filled in the shape with a deeper line. And with every tresspassing done that I could respect the coming sensations—that buzzing feeling of skin, that growing sense of tinnitus, a restless state of being—adjusting my expectations and communicating, my inner child grew safer.

And she just keeps on getting louder in how she plays, and finds her joy. She didn’t need me to pick a fight, show her how to get over it, or escape into a distraction.

She needed me to simply take her seriously, and into my arms.

I started writing about trust, this fickle inner compass that guides and directs each of my steps taken forward. I went back into a story of my life I’ve never shared before, and I’ve not thought of in years, more than a decade. I thought—how random.

Now an adult myself, I wish there was a way to give clear direction to oneself. To say: “Hold up, my compass is acting up here. Are we in cognitive dissonance?”

To which my inner child would reply: “…Uhm. What is coginissive dinance?”

“It’s that feeling you feel when what you hear is not what you see, what you see is not what you feel, and what you feel is weird.”

“Hmm… mhm… ok.”

Then she’d reach her tiny palms for my face, pull close into my eyes, and ask:

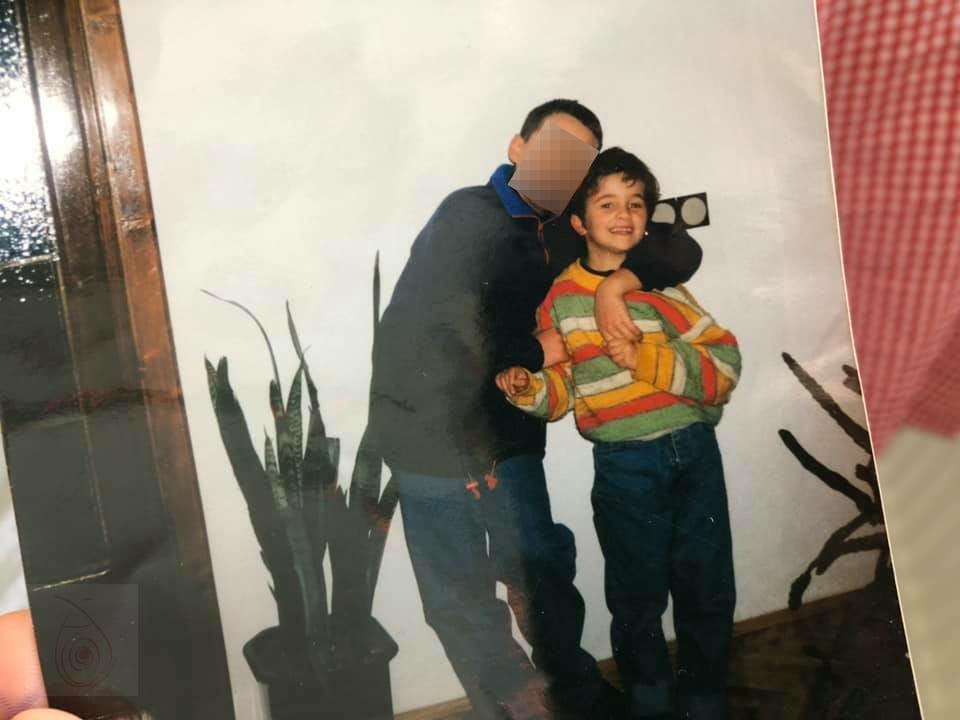

“Ani Buuuuubë, how are youuuuu?”

.

.

.

Dashni,

Bubamarrë 🐞

Thank you for steadying this wave along with me. May it have brought you at least some validation, if not relief. Take care of yourselves, friends.

Such a beautiful piece Agnesa. I feel your whole heart in it <3

I especially love this line: "At a very young age, I learned that reality is an embroidery sown by the hands most apt to wind its threads." Wow!